December 11, 2018

Day 19: Ingo Burghardt, Australian Museum Sydney

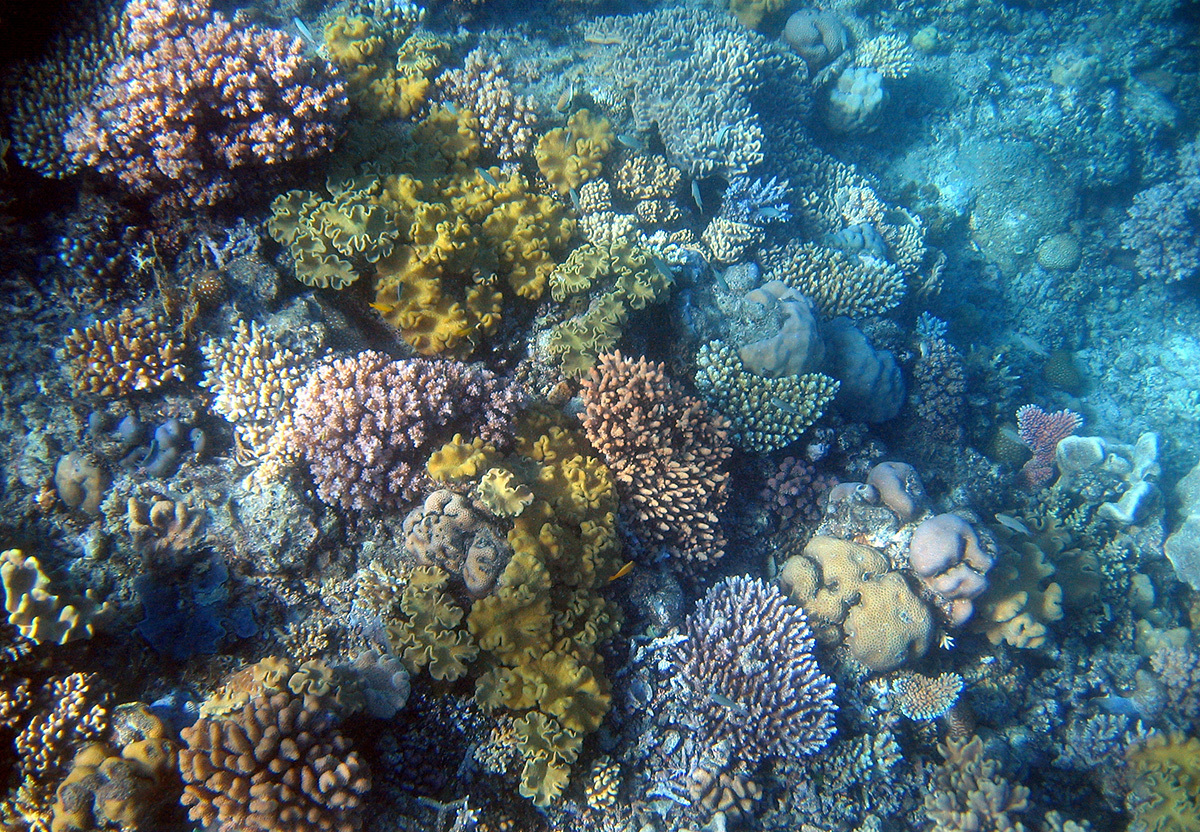

What sort of image comes up when you think of ‘coral reefs’? I’m pretty sure you imagine the colourful coral reefs of the crystal-clear tropical waters? You are right and probably share this idea with the vast majority of people. But open your mind, there is another type of coral reefs thriving in a place where you would normally not expect them: the deep sea!

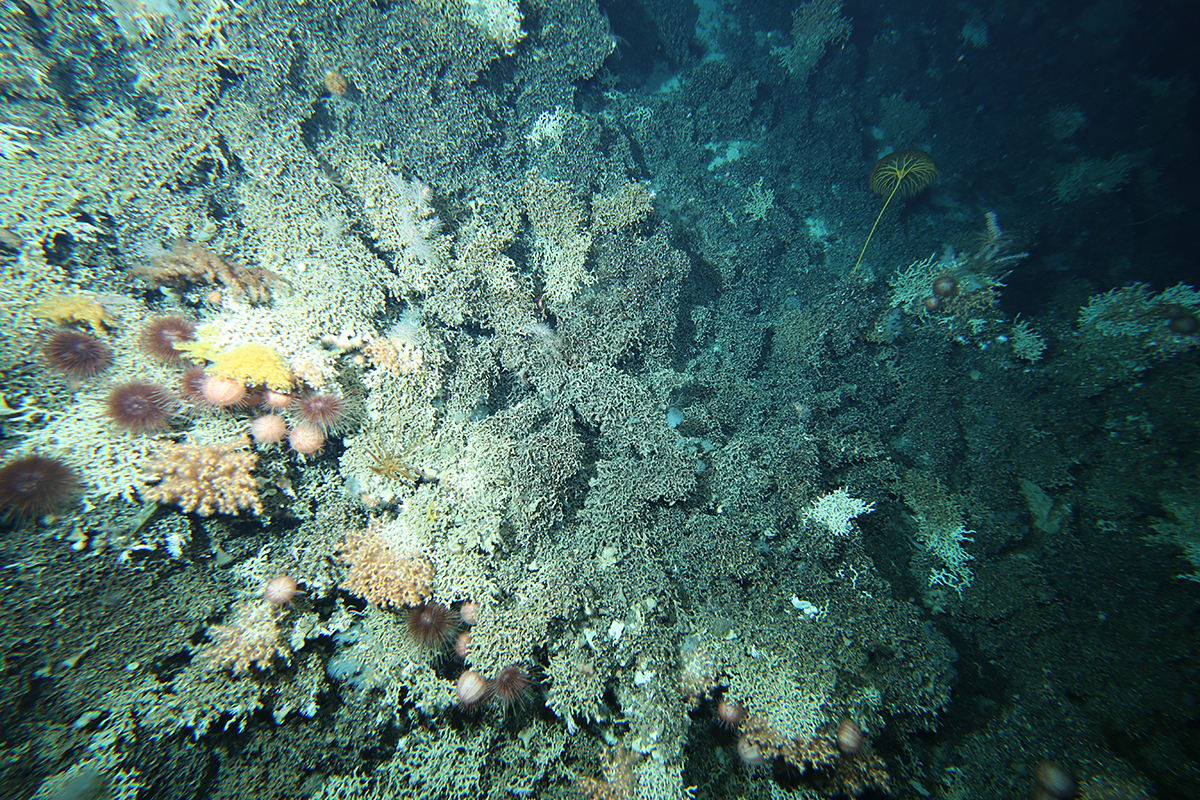

Deep-sea coral reefs are found worldwide in the cold and dark waters of the deep sea (50–1000 metre depths in high latitudes, down to 4000 m in the tropics). They have been known since the 18th Century but knowledge of their distribution, ecology and high biodiversity remained largely unknown for a long time.

For me as a marine zoologist who has previously focused on organisms in shallow-water tropical coral reefs it is fascinating to explore these ‘other reefs’ and to discover the differences and similarities. The Tasmanian Seamounts are the perfect area to study these cold-water reefs and I haven’t been disappointed. I’ve seen a mind-blowing biodiversity of most invertebrate groups. Some of the camera tow operations also showed reef structures that looked stunningly similar to the ones I’ve seen in tropical shallow waters. But more on that later.

Two environmental factors that differ dramatically between deep-sea reefs and shallow-water reefs are light and temperature. The lack of light in the deep sea means all the corals are ‘azooxanthellate’. This means they don’t have the algal symbiotic partners (‘zooxanthellae’) that supply tropical shallow-water reefs with photosynthetic products and energy (which is necessary in the nutrient-poor shallow tropical waters).

Deep-sea corals mainly rely on zooplankton and dissolved nutrients from sources outside their habitat for their energy supply. As such they are found in places such as seamounts, where currents deliver food supplied by upwelling nutrient-rich water. Deep-sea coral reefs thrive in temperatures of 4–12○C. In contrast, shallow-water coral reefs exist in the clear, warm waters of the tropics and subtropics. Both kinds of corals, however, need hard substrates to settle on and that is one of the reasons why they are mainly found on the edges of continental shelves, slopes, ridge systems and seamounts. You won’t find them on the slippery sediments of deep-sea plains.

Corals in general are ‘ecosystem engineers’. They build complex three-dimensional frameworks that provide sub-habitats for a diversity of other organisms. In the deep-sea, this job is done by a relatively small proportion of the overall hard coral, or scleratinian, species. On the Tasmanian seamounts the main reef-building species is Solenosmilia variabilis. Solenosmilia is very important because it supports a high diversity of animals (about 850 animal species). On a single survey, 299 species of animals were sampled from these seamounts.

Corals, molluscs and fish are generally much less diverse in deep-sea coral reefs. I specialise in nudibranchs (molluscs also known as ‘sea slugs’) and I could see this difference first hand: we’ve only found five nudibranch species so far, a pretty low number compared to what you would expect in tropical coral reefs. However cold-water reefs are also considered major speciation centres, especially on seamounts, with often a high degree of endemism. On a 2007 survey 24–43% of the species found on the Tasmanian Seamounts were new to science and are endemic to this region. Most were associated with Solenosmilia.

Tropical and deep-sea coral are both vulnerable to human pressures. In general, deep-sea environments are less favourable than shallow waters, but at the same time more stable. Compared with tropical species, deep-sea invertebrates (including reef-building corals) can grow extraordinary slowly and they often have very long lifespans. The slow growth of deep-sea corals and their fragility make them especially vulnerable to disturbance by human activities such as fishing and mining, and slow to recover. Tropical corals are relatively fast-growing and more heavily impacted by high water temperature bleaching events (driven by climate change), agricultural runoff and outbreaks of crown of thorns starfish. Both coral types are heavily affected by climate-change-related ocean acidification, which affects coral growth and weakens the coral skeleton framework.

Notes on today's activities from Marine Biodiversity Hub Director, Nic Bax . . .

Today started with an early beam trawl (‘Candace’s tow’) at the 2 am shift change, leaving the biologists to choose between sleep after working for 12 hours straight or getting their hands on the daily catch. Most decided that sleep could wait, while working on fresh material from the deep sea was not an experience that comes along very often in a biologist’s life. Candace’s tow was targeted at Andy’s Hill from 730 to 900 m where a large variety of golden corals (Chrysogorgia) had been seen on video. The trawl did not disappoint and although overall diversity was quite low (only five molluscs, one of which had not been seen before), there were four species of Chrysogorgia, one rather surprisingly turning out to be the ‘yellow fluffy stuff’ we have had trouble identifying on video – or at least one type of that loose classification

The abundance of Chrysogorgia also provided a good selection of the animals that live in this finely branched octocoral, including an obligate shrimp possessing an oversized claw with features just the right size to clean the coral branches. Interestingly some of the Chrysogorgia which are relatively fast growing and reached 30-40cm in this sample, showed signs of having been broken off close to the base as did some of the non-walking stalked crinoids in the catch, suggestive of regrowth after a traumatic event, such as a trawl passing through, but further examination back in the lab will be required.

Then it was back to the deep towed camera, where we completed the shallower background transects coming down off the slope in our continuing search for an upper limit to the distribution of stony corals in this area. Camera tows started at 650-850 m often characterised by diverse communities including gold corals, black corals, crinoids and sponges. A few Solenosmilia clumps were seen starting at about 900m, sometimes preceded by what appeared to be dead coral matrix, and extending to the end of transects at 1000-1100 m depth where isolated clumps continued to be seen on some of the boulders or other raised features.

Next up for the day was fishing for the basketwork eel on Patience seamount. The only deepwater spawning aggregation of the basketwork eel was detected on this seamount in April 2015, and we were keen to understand whether or not this spawning aggregation extends throughout the year. An initial deep towed camera survey failed to detect the aggregations observed previously, although eel numbers were slightly higher than in other places surveyed this trip. Admit much bemusement from onlookers a deep sea fishing rod and electric reel were set up with 3000 m of line, a 5 kg sinker and 10 hooks baited with squid. After 10 minutes the sinker reached its target depth of 1100 m, while the ship used its dynamic positioning and bow thruster to maintain station to within a reported better than 1 m accuracy. After 20 minutes of anxious waiting and a 10 minute return trip, one eel was caught – a female with immature eggs. The ovary was preserved for subsequent fixing and slicing at which time a more precise estimate of the stage of spawning development will be obtained.

To finish the day, the two BRUVs were redeployed at Patience seamount and we steamed across to Sisters in search of the granite settlement plates left there 10 years ago. If we can find and photograph those plates, it will provide some indication of how organisms at these depths recruit to baser substrate.

All in all a diverse and rewarding day, enhanced by a school of 20-25 sperm whales that swam by close to the ship, and fresh-squeezed orange juice for breakfast.

- Log in to post comments